Introduction

This website contains the image assets and materials discovered by the "Task Force to Review the Naming of the University Library" during their recent research and is outlined in detail in the report. These materials contain antisemitic, racist, violent, offensive, and disturbing language and imagery; the materials are for informational purposes and do not represent the views of California State University, Fresno.

The content sections of this site are:

Please feel free to explore the exhibition items in more detail by clicking on any of the images below. We also share important information in the Access to the Collection Items and Acknowledgements sections.

IMPORTANT: All materials found in this website are covered by copyright, as outlined in the footer of this website. Anyone who requires a transcript or machine-readable copy of the original letters available on this site, please contact the Special Collections Research Center at scrc@mail.fresnostate.edu or call us at 559.278.2595.

Supporting Materials

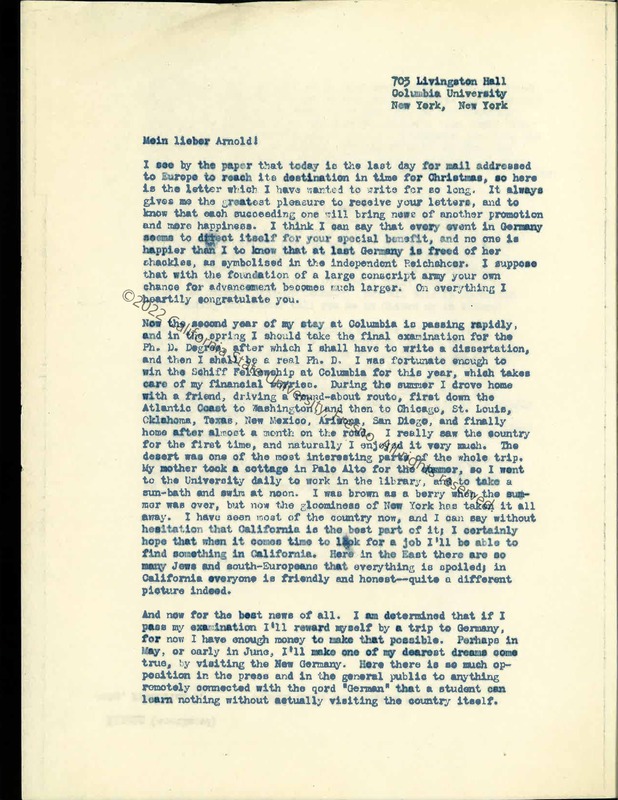

Columbia University Period (1934-1936)

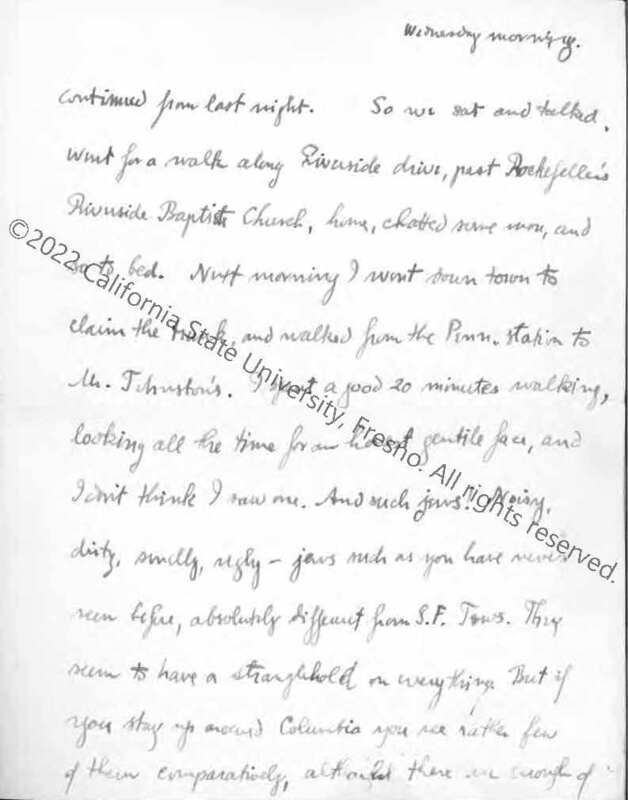

Letter to His Mother, 1934

The first overt evidence of Henry Madden’s antisemitism emerged while he was a graduate student at Columbia University in New York City. Writing to his mother in September 1934, just a few days after arriving in the city, Madden described his initial impressions, reserving particular ire for New York City’s demographics:

I spent a good 20 minutes walking, looking all the time for an honest gentle face, and I don’t think I saw one. And such Jews! Noisy, dirty, smelly, ugly—Jews such as you have never seen before, absolutely different from S.F. Jews. They seem to have a stranglehold on everything.

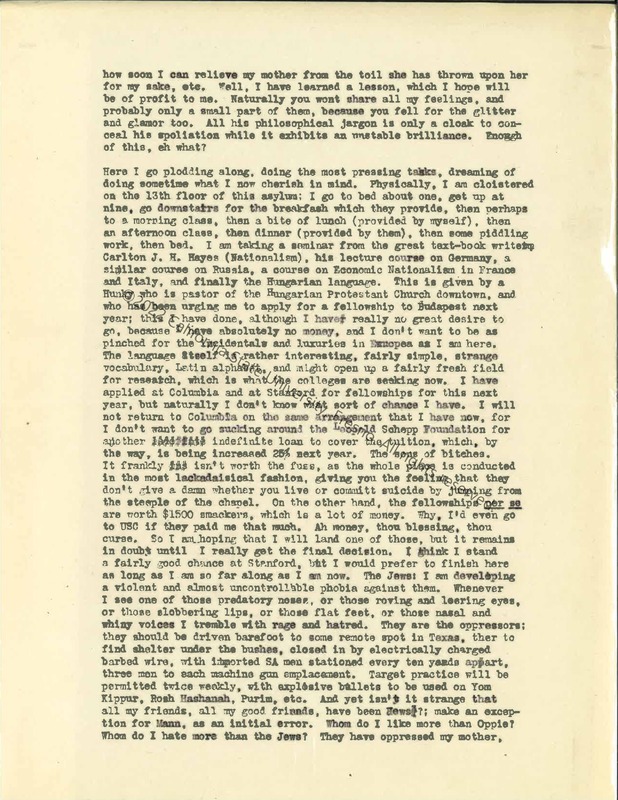

Letter to a Friend, 1935

In 1935, Madden told a friend about his increasingly violent fantasies about the country’s Jews in language that would undoubtedly have shocked the conscience of most Americans. Madden wrote:

The Jews: I am developing a violent and almost uncontrollable phobia against them … They are the oppressors; they should be driven barefoot to some remote spot in Texas, ther [sic] to find shelter under the bushes, closed in by electrically charged barbed wire, with imported SA men stationed every ten yards apart, three men to each machine gun emplacement. Target practice will be permitted twice weekly, with explosive bullets to be used on Yom Kippur, Rosh Hashanah, Purim, etc.

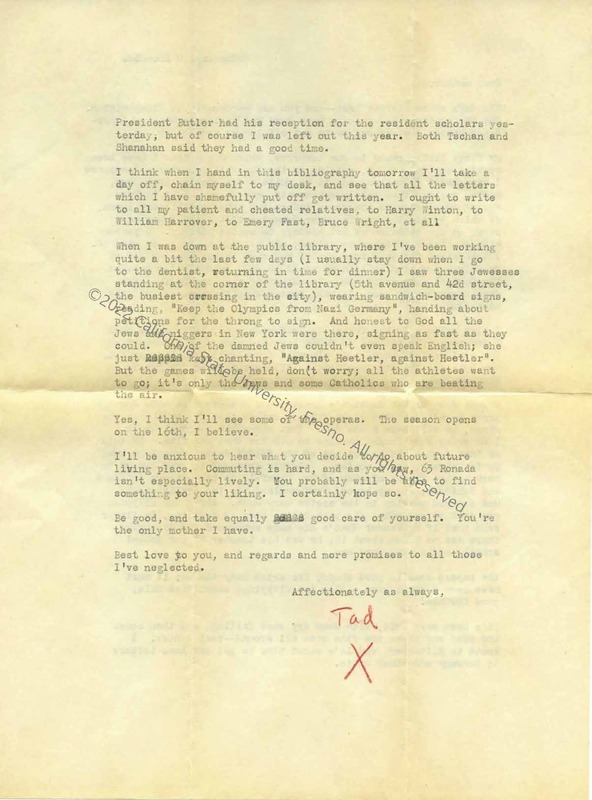

Letter to His Mother, 1935

By late 1935, the Roosevelt Administration and the American Olympic Committee (AOC) were feeling the effects of a public pressure campaign to boycott the upcoming 1936 Berlin Games as a means of showing international concern for the regime’s discriminatory actions against its Jewish population. The AOC’s president, Avery Brundage, opposed the idea of boycotting the games and argued that politics should be kept separate from sports. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Madden agreed with Brundage and supported American participation in the games. He also blamed Jews for instigating the campaign. In December 1935, he described the campaigners in particularly demeaning terms to his mother and included a racist remark about Black New Yorkers in the process:

When I was down at the public library, where I’ve been working quite a bit the last few days … I saw three Jewesses standing at the corner of the library (5th avenue and 42nd street, the busiest crossing in the city), wearing sandwich board signs, reading, “Keep the Olympics from Nazi Germany”, handing about petitions for the throng to sign. And honest to God all the Jews and niggers in New York were there, signing as fast as they could. One of the damned Jews couldn’t even speak English; she just kept chanting, “Against Heetler, against Heetler”. But the games will be held, don’t worry; all the athletes want to go; it’s only the Jews and some Catholics who are beating the air.

Letter to a Friend, 1935

In a letter to a friend, Madden attributed the American campaign to boycott the 1936 Berlin Olympics to Jewish Americans:

Unless you have been to New York, you cannot imagine how bitterly Hitler is hated by every Jew. They have naturally bent every effort to prevent American participation in the games, but I know that every athlete who would have a chance of going is decidedly in favor of American participation.

This assertion was false, as the boycott campaign had supporters from a wide swath of American society. In the end, the United States took part in the Berlin Games, providing Hitler’s government with a much-needed propaganda coup. Madden rejoiced.

Travels in Europe Period (1936-1937)

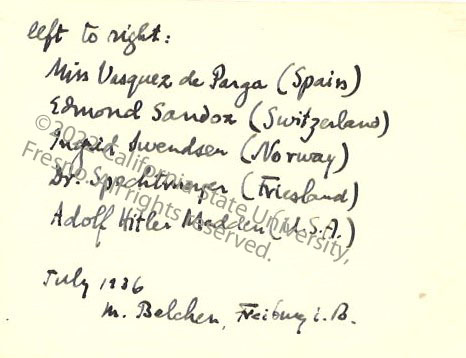

“Adolf Hitler Madden” Photograph, 1936

In the summer of 1936, during his time as a student at the Royal Hungarian University of Budapest, 25-year-old Henry Miller Madden traveled extensively throughout Germany and visited many prominent German sites. Madden proudly poses on Mount Belchen near the Black Forest, giving the Hitler salute and placing a toothcomb mustache under his nose. The caption on the back of the photograph reads “Adolf Hitler Madden (U.S.A.)”

Madden Posing in Saxony, 1936

In Saxony, Madden posed under a festival banner and gave a Nazi salute for the camera.

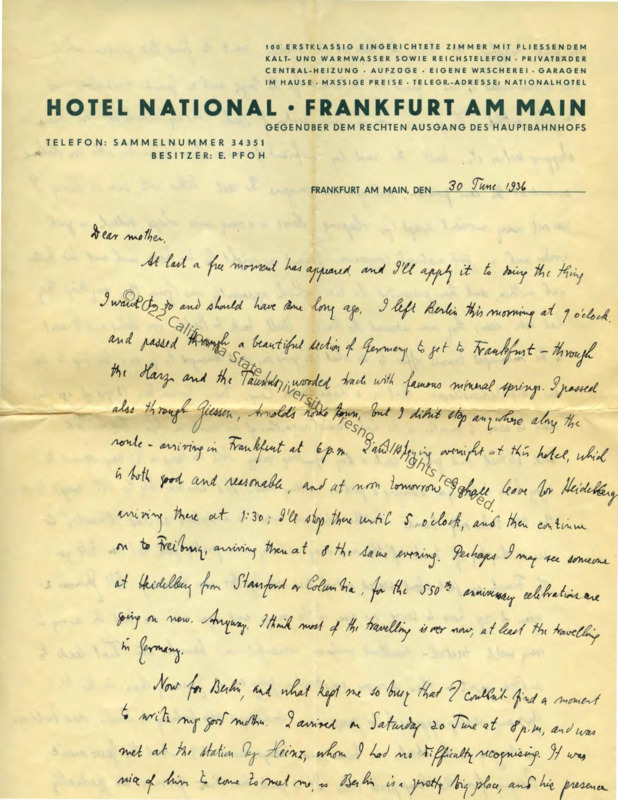

Letter to His Mother, 1936

On June 30, 1936, Madden wrote to his mother after departing Berlin, sharing his impressions of the city and the Third Reich. This letter hardly reflected the objective reality of life under the regime. There had been devastating physical, economic, and political violence against Jews by 1936. Madden would have been very aware of these developments. Yet his letter minimized Nazi brutality, while at the same time downplaying the toll of other Nazi criminal policies, including those that allowed Germans to, as Madden put it, take over “businesses formerly controlled by Jews.” He ended the letter with “Heil Hitler!”

Stanford and the War Period (1937-1947)

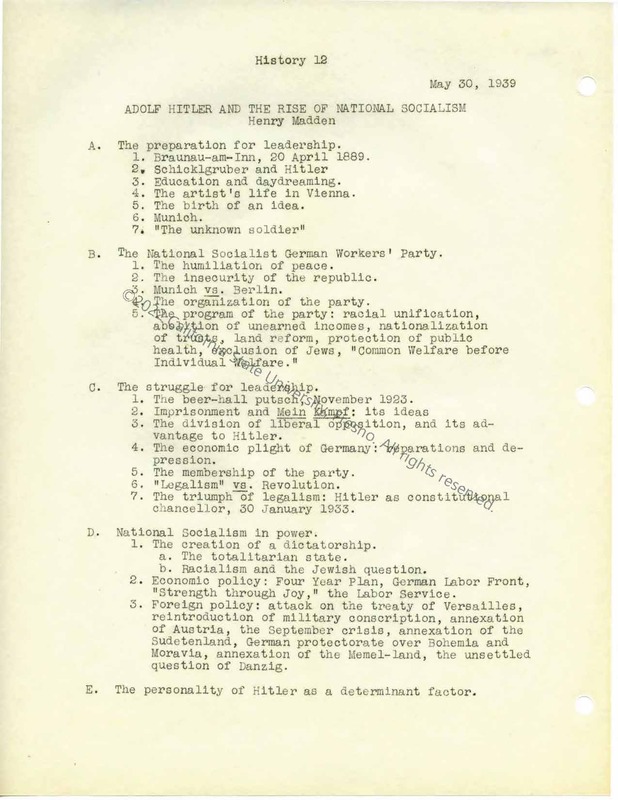

Outline for Madden’s Lecture, “Adolf Hitler and the Rise of National Socialism,” 1939

Madden served as a history lecturer at Stanford University from 1937 to 1942. A part of a team of instructors who taught the university’s large Western Civilization survey, he gave a lecture on Hitler and the rise of National Socialism at least three times: in 1938, 1939, and 1942. In these lectures, Madden was not as openly celebratory of the Führer or his regime as he had been in his mid-1930s correspondence. But the lectures nonetheless betray Madden’s abiding habits of highlighting Nazi Germany’s economic success, justifying some of its antisemitic grievances, and sanitizing the regime’s most repulsive policies.

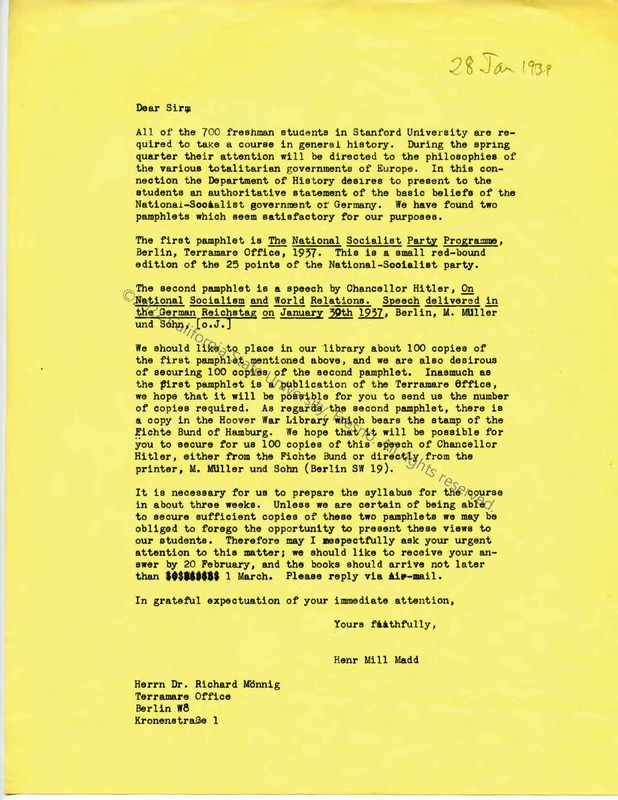

Letter to a Nazi Propaganda Publisher, 1939

While serving as a lecturer at Stanford University from 1937 to 1942, Madden began corresponding with Richard Mönnig of the Terramare Office, a publisher of Nazi propaganda. Stanford’s Department of History, Madden wrote Mönnig on January 28, 1939, “desires to present to the students an authoritative statement of the basic beliefs of the National-Socialist government of Germany.” He asked Mönnig to send him 100 copies of two pamphlets—the National Socialist Party Programme and a 1937 speech by Adolf Hitler—to be deposited in the department’s library for use in the Western Civilization course Madden helped teach. Mönnig seems to have complied with this request because these two pamphlets appear on that spring’s Western Civilization syllabus.

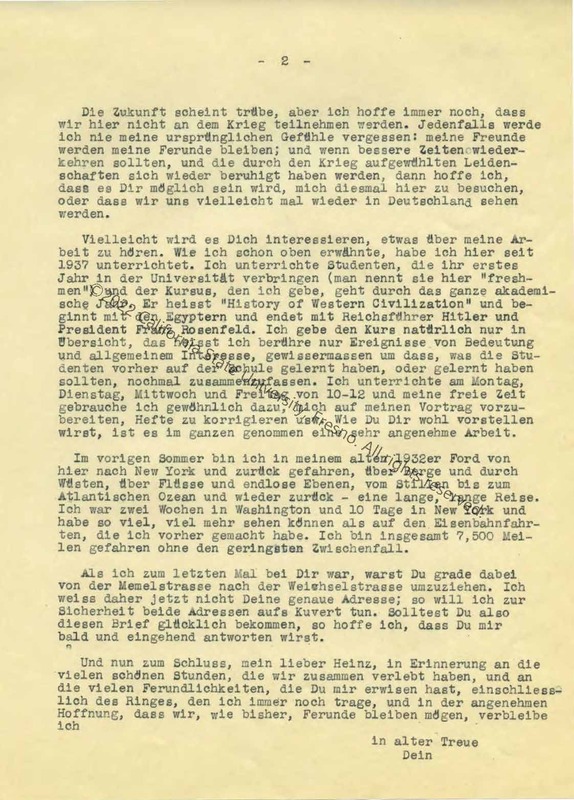

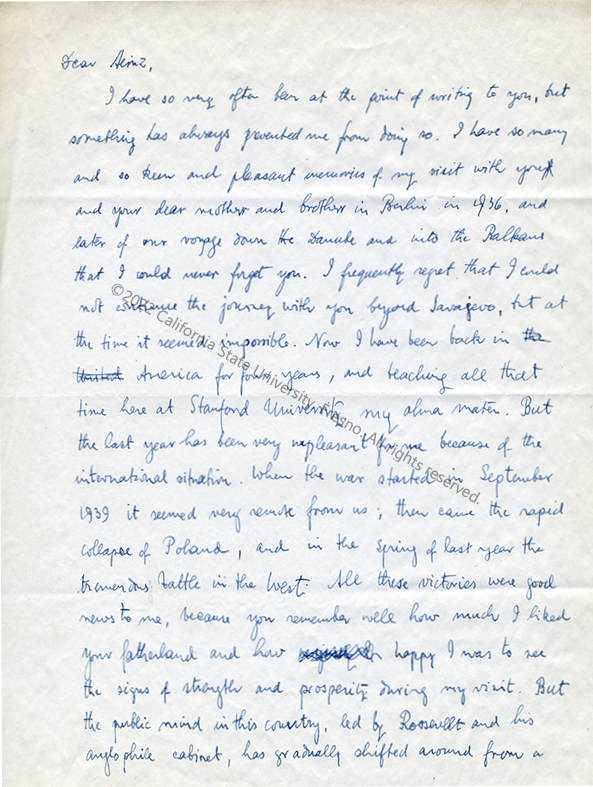

Letter to a German Friend, 1941

On July 19, 1941 Henry Madden wrote to his German pen pal, Heinz Rüdiger, informing him that “while the international situation” was “very unpleasant” for him, he felt differently about “the rapid collapse of Poland” and “the tremendous battle in the West” in the spring of 1940. Madden celebrated German military progress and proclaimed that “all these [German] victories were good news to me”.

Ich habe mich über all diese deutschen Siege sehr gefreut … denn du wirst dich daran erinnern, wie sehr mir dein Vaterland gefiel … Die Zukunft scheint trübe, aber ich hoffe immer noch, dass wir hier [in Amerika] nicht an dem Krieg teilnehmen werden [gegen Deutschland]. Jedensfalls werde ich nie meine ursprünglichen Gefühle vergessen: meine [deutschen] Freunde werden meine Freunde bleiben … verbleibe ich in alter Treue

“I have been very happy about all of these German victories … because as you will recall, I liked your fatherland very much … the future seems bleak, but I am still hopeful, that we [in America] won’t participate in the war [against Germany]. In any case, I will never forget my original feelings: my [German] friends will remain my friends … I remain loyal in old times” (trans. Amila Becirbegovic)

Arrival at Fresno State and Collection Building

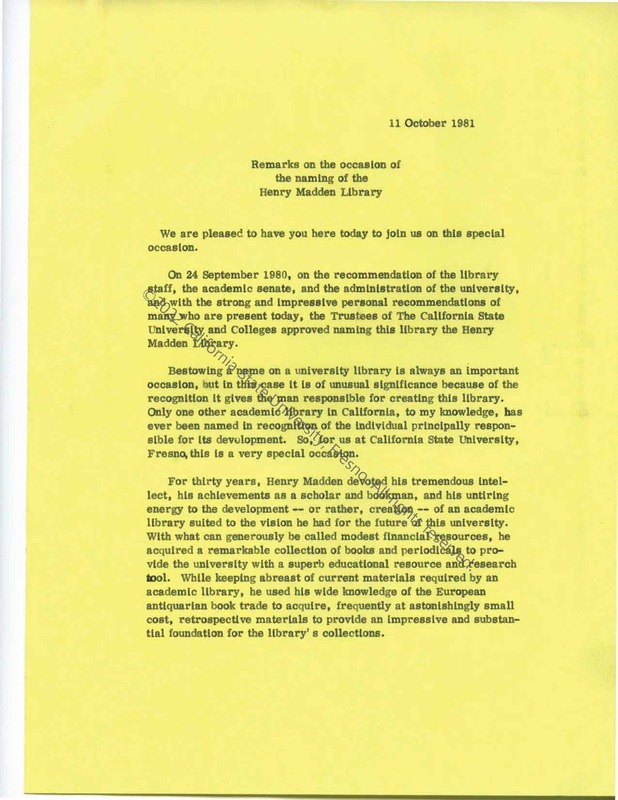

Fresno State Librarian Lillie Parker’s Remarks on Naming of Madden Library, 1981

At the ceremony celebrating the naming of the Henry Madden Library on October 11, 1981, Lillie Parker highlighted Madden’s success at building the library’s collection during his thirty-year career. Parker and other supporters of the naming decision agreed that the library’s collection was Madden’s most enduring legacy. Several librarians have observed that he transformed a teacher’s college library into a research library unrivaled in the CSU system. There is no evidence that these individuals were aware of Madden’s antisemitism or of his 1930s support of Hitler and the Nazi regime.

Postwar Refugee Work Period (1948-1949)

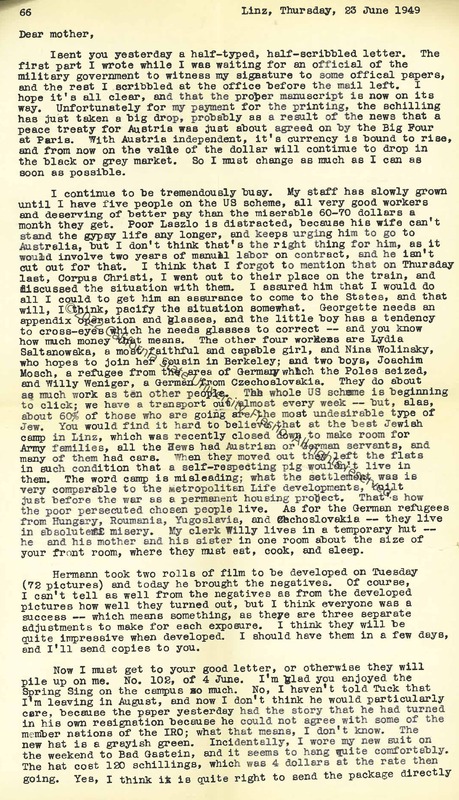

Letter to His Mother, 1949

From 1948-1949 Madden worked at the International Refugee Organization in Linz, Austria. There he primarily aided in the transport and resettlement of displaced persons. In the immediate post-war period Europe established displaced persons camps, mainly in Austria and Germany, for refugees from Eastern Europe and for former concentration camp inmates. In the summer of 1945, Earl G. Harrison, US representative on the Committee on Refugees, published The Harrison Report and detailed the horrific conditions of the displaced persons camps. The report outlined that many of the buildings were uninhabitable, the people were treated like inmates and were starving, left without resources or food. Despite the consensus of the horrible condition of the displaced persons camps, Madden writes deeply antisemitic propaganda about displaced Jews in 1949.

We have a transport out almost every week—but, alas, about 60% of those who are going are the most undesirable type of Jew. You would find it hard to believe that at the best Jewish camp in Linz, which was recently closed down to make room for Army families, all the Jews had Austrian or German servants, and many of them had cars. When they [Jews] moved out they left the flats in such condition that a self-respecting pig wouldn’t live in them. The word camp is misleading; what the settlement was is very comparable to the Metropolitan Life developments, built just before the war as a permanent housing project. That’s how the poor persecuted chosen people live. As for the German refugees from Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia—they live in absolute misery.

Anti-Censorship Campaigns

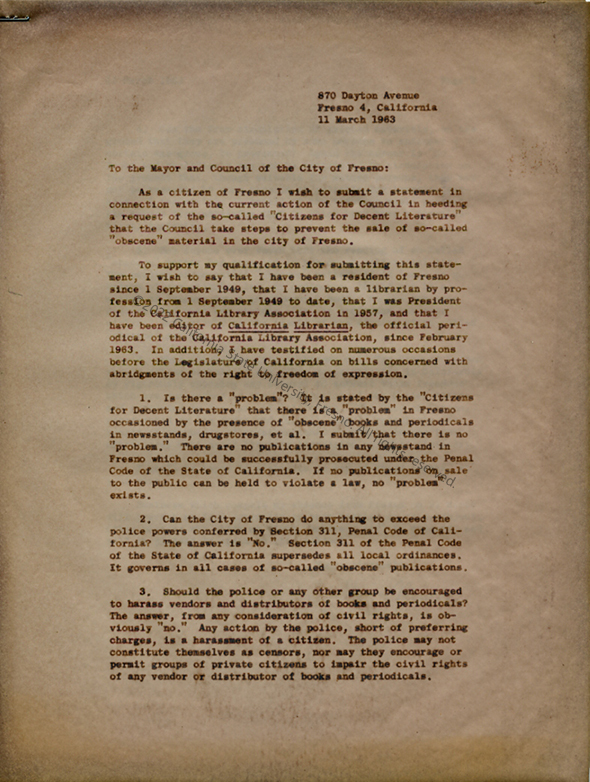

Letter to Fresno Mayor and City Council, 1963

In 1963, as part of his years-long fight against censorship, Madden co-founded and became chair of the Fresno Freedom to Read Committee. In this capacity, he wrote to the mayor and city council, urging them to oppose a censorship campaign underway in Fresno. Madden never reckoned with his mid-1930s embrace of a book-burning regime during these years. The contradiction is noteworthy, particularly since Madden’s anti-censorship work was cited as among his most important professional legacies and a reason to name the library in his honor.

Madden’s Later Views on Race

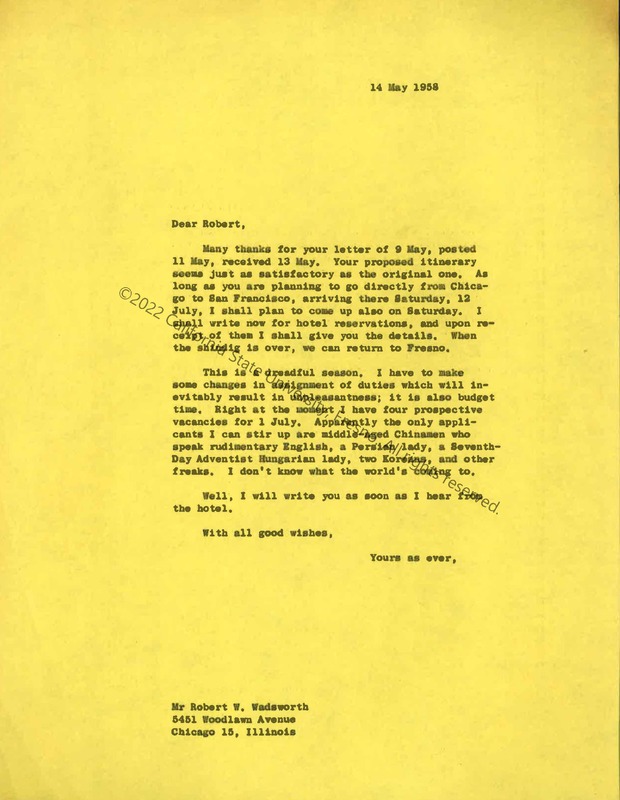

Letters to Fellow Librarians, 1958 and 1968

In 1958, Madden described his hiring challenges to a fellow librarian this way:

Apparently the only applicants I can stir up are middle-aged Chinamen who speak rudimentary English, a Persian lady, a Seventh-Day Adventist Hungarian lady, two Koreans, and other freaks. I don’t know what the world’s coming to.

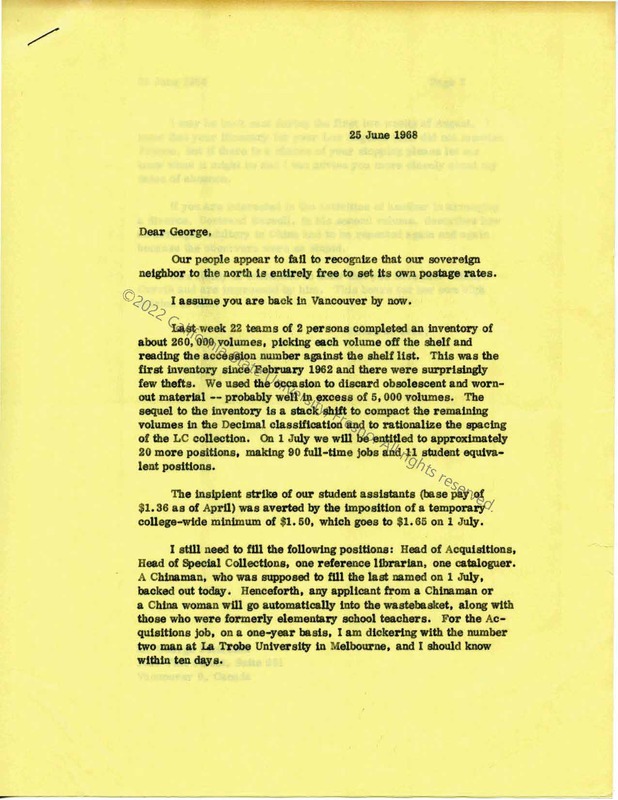

Ten years later, he complained of a Chinese-American who had been hired as a cataloger but then decided not to take the job:

Henceforth, any applicant [sic] from a Chinaman or a China woman will go automatically in the wastebasket, along with those who were formerly elementary school teachers.

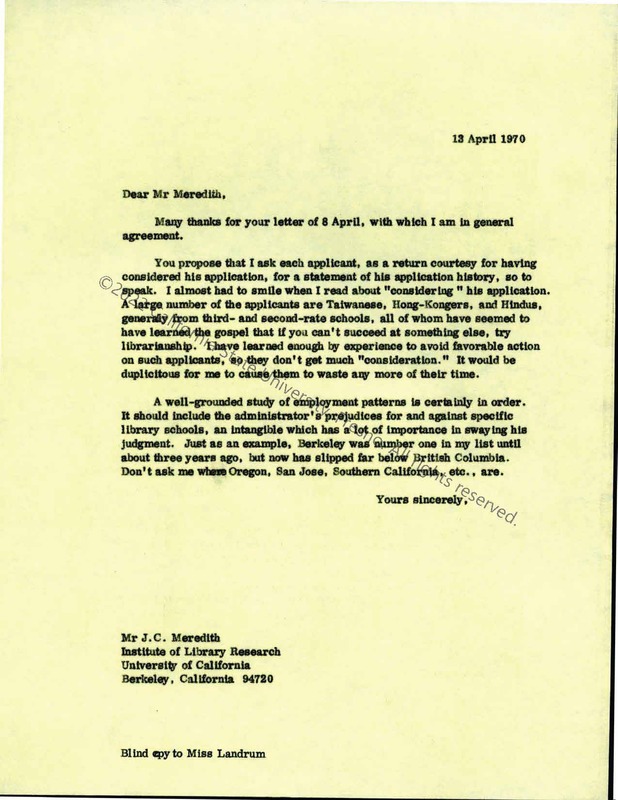

Letter to a Colleague, 1970

Madden’s racial prejudices against people of color demonstrably informed his hiring practices at the library. Several times during the 1950s and 1960s Madden indicated that he did not look favorably upon Asian-American job applicants. Although there were, in fact, several librarians on the staff with Chinese and Japanese surnames during these years, by his own account these prejudices did impact his personnel decisions, as this 1970 letter to a Berkeley colleague reveals.

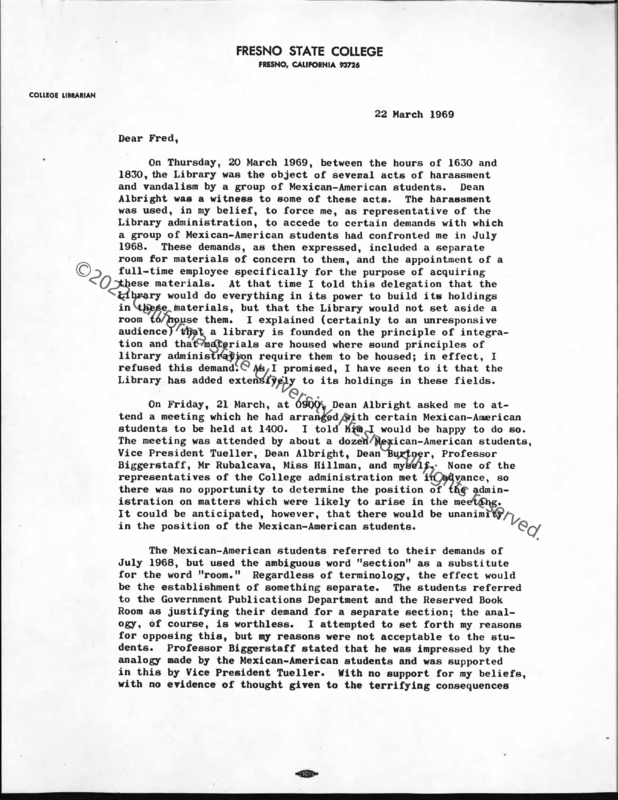

Letter to Fresno State President Frederick Ness, 1969

In March 1969, a dozen Chicano students engaged in civil disobedience because Madden had not adequately responded to their requests to diversify the library’s holdings, checking out a large number of books, for example, and then immediately returning them. Library staff noted that the students “were very peaceful,” but in this letter to Fresno State President Frederic Ness, Madden characterized their actions as “harassment and vandalism.” As a result of the controversy, Madden offered to resign his position but later changed his mind.

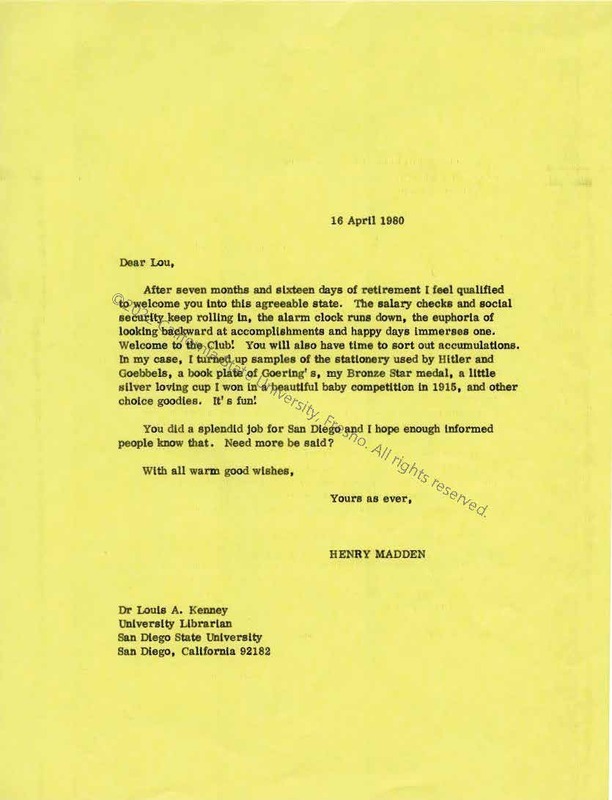

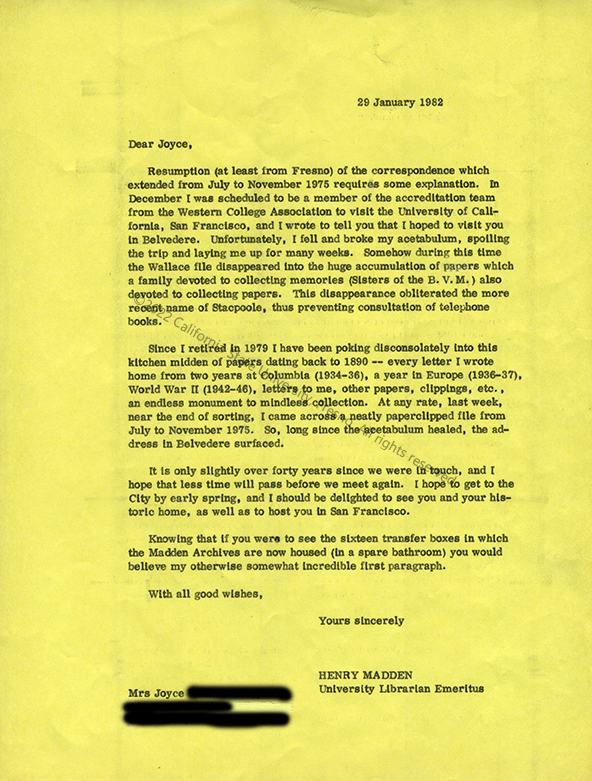

Letters to Colleagues, 1980 and 1982

Upon his retirement in 1979, Madden began sorting through his personal papers and memorabilia with an eye toward donating them to an archive. As these letters show, Madden was aware of the materials he had amassed over the years, and as a historian and a librarian, Madden knew better than anyone that future researchers would see the items he had saved. He died fully aware of the contents of his personal papers, in other words, and yet this knowledge did not inspire self-reflection about earlier Nazi sympathies, his antisemitism, his racist remarks, or hiring practices.

Postwar Antisemitism and Nazi References

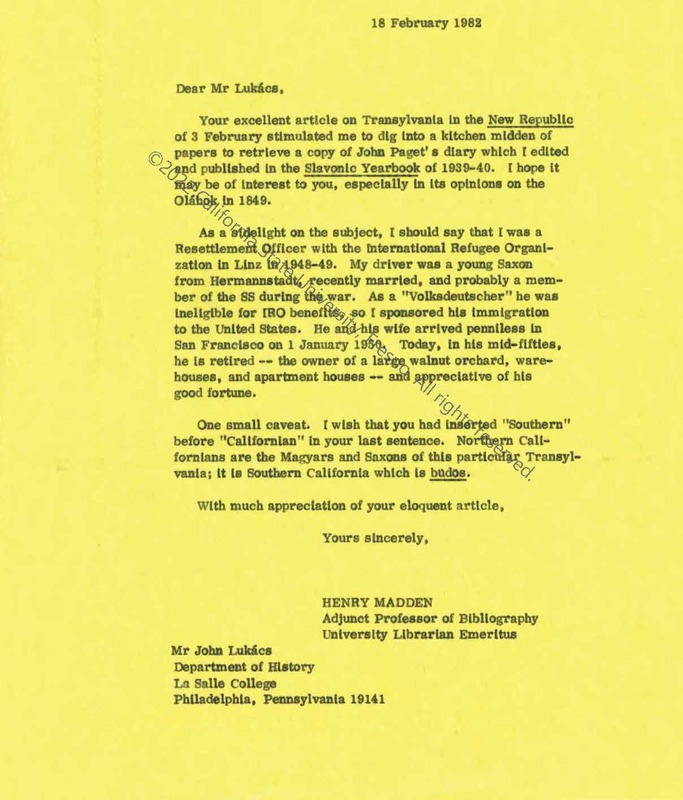

Letter to John Lukács, 1982

Months before his death in 1982—in one last revealing act—Henry Madden wrote in a letter to historian John Lukács that he had once helped a man immigrate to the U.S., a man who was “probably a member of the SS during the war.” The revelation is shocking, particularly in an unsolicited letter to a stranger. The most direct evidence that we have of Madden aiding former Nazis, this letter tells us a great deal: Madden thought he had helped a soldier who served the Nazi regime achieve the American Dream, and he had no regrets.

As a sidelight on the subject, I should say that I was a Resettlement Officer with the International Refugee Organization in Linz in 1948-49. My driver was a young Saxon from Hermannstadt [in Transylvania], recently married, and probably a member of the SS during the war. As a ‘Volksdeutscher’ he was ineligible for IRO benefits, so I sponsored his immigration to the United States. He and his wife arrived penniless in San Francisco on 1 January 1950. Today, in his mid-fifties, he is retired—the owner of a large walnut orchard, warehouses, and apartment houses—and appreciative of his good fortune.

Additional Documents

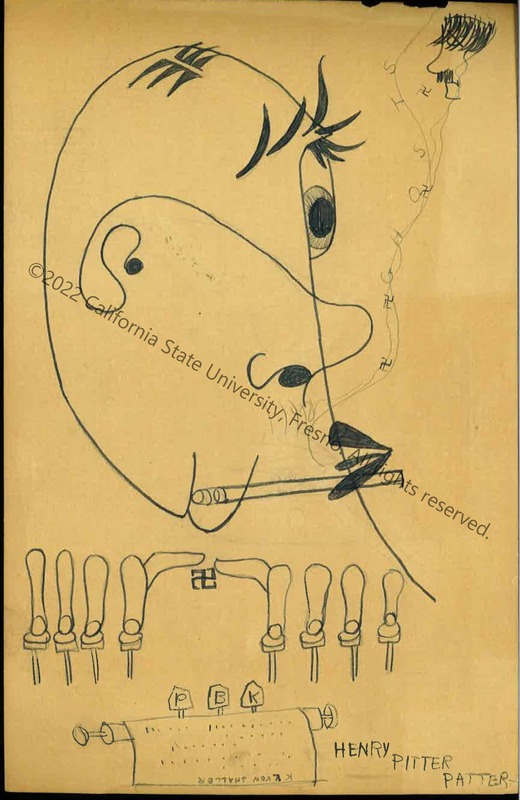

Drawing 1

A depiction of a Dadaesque Madden floating, disembodied over a typewriter with a dangling swastika among the keys. Madden is shown smoking a cigarette while the smoke plume forms the letters “G H O S T S” leading up to a tiny swastika and a ghostly Hitler head floating in the right-hand corner. The inscription at the bottom reads “Henry Pitter Patter” alluding to the sound of the keys as someone types. PBK likely stands for the abbreviation of paperback and the name on the typewritten page reads Karl August Schaller, who was a well-known German writer and published The Encyclopedia of Research in 1812. This drawing alludes to the specters of Madden’s National Socialist past.

Access to the Collection Items

The Henry Miller Madden papers and the Fresno State Library records are open for research by anyone at the Special Collections Research Center on the fourth floor, south wing of the Fresno State Library. For more information about the Henry Miller Madden papers, please see this guide.

Appointments are available Monday through Friday, 8 a.m. through 5 p.m. To make an appointment to view any materials, please contact Special Collections at 559.278.2595 or email us at scrc@mail.fresnostate.edu.

Acknowledgements

The contextualization and captions were authored by Dr. Amila Becirbegovic, Dr. Bradley Hart, Dr. Ethan Kytle and Dr. Blain Roberts. The German translations were provided by Dr. Amila Becirbegovic.

This project was made possible through the work of the Digital Services and Information Technology team and with the help of the Special Collections Research Center. Special thanks to Karina Cardenas, Renaldo Gjoshe, Tammy Lau, Sarah McDaniel, Julia Moore, Steven Orr and Adam Wallace and the entire library staff for their contributions and work on this project.